In financial lore, IPOs are supposed to be a risk-free investment, especially in India. Strong stock-market momentum after the Covid-induced collapse of early 2020 attracted fresh institutional interest. Many of India’s startup jewels are replicas, up to a point, of successful tech companies elsewhere. The Indian heritage of using frugality to overcome adversity adds a certain flair to a pervasive entrepreneurial spirit. What could possibly go wrong?

Investing in Indian IPOs has in fact been a tough slog. The most prominent example is Paytm, the mobile payments giant. The stock price is down about 65% from its November 2021 IPO. Other missteps include:

Zomato, a delivery company, has seen its stock fall near 37% since its listing in July 2021.

Nykaa, an ecommerce play, has performed poorly. Its shares are off some 32% since its debut last year.

PolicyBazaar, a fintech name, has seen its stock drop almost 44% since its listing in November 2021.

The carnage is not limited to Mumbai. India-based Freshworks, a software-as-a-service enterprise, has seen its stock fall 57% in the wake of a July 2021 listing on NASDAQ. Curiously, Sequoia Capital, the venture-capital behemoth, just bought some $95 million in stock, according to a US Securities and Exchange Commission filing, presumably to save face with its limited partners. In 2018, Sequoia Capital made a generous late-stage funding commitment to the young company.

The BSE Sensex Index, a benchmark for India-based shares, has been up about 15% since the beginning of the third quarter 2021. The downside is issue-specific.

The Securities and Exchange Board of India has stepped in to stabilize the local venture-capital market. It is now asking IPO-bound firms to justify their valuation measures using key performance indicators, not just traditional financial ratios. Industry insiders admittedly are uncertain how this new disclosure framework will work in practice. A Reuters article suggests that requirements may include figures like the number of downloads or average time spent on an internet-based platform.

Disappointing IPO performance, paired with a deteriorating global backdrop, may bode poorly for dynamic Indian companies exploring monetization strategies. We take a different view. The turbulence, however painful for stock-market investors, is likely to build a better foundation for this startup ecosystem. There may be a rudimentary parallel with the 2000 tech wreck in the US, which led to a more-settled Silicon Valley, at least for a period of time.

In our view, there are three reasons why certain India-based IPOs have faltered. The local press often calls them new-age startups. That term may be an oxymoron:

Market Structure. The venture capital market is dominated by a handful of super-sized names. Sequoia Capital is one example, Accel and Tiger Global Management should be included on the list. The volume of capital at play lends a wave of credibility to their activities—often with a narrow set of investible companies—until that wave becomes, well, a closeout.

Valuation Standards. Fundamental analysis among Indian startups is often based on international peers, rather than domestic standards. That is dangerous, but it is a posture that is self-serving to companies and their bankers. A so-called international valuation measure is as mythical as a unicorn. Among the considerations, every market—major and emerging—has this thing known as a country risk premium.

Startup Hype. Scaling a digital company through price discounting is quite different than running a sustainable business model. Still, early successes may have clouded the commercial outlook in some corners of Indian business. Public markets, meanwhile, have this uncanny way of exposing masters of the universe as everyday folk, confronting the same challenges that have faced companies for centuries.

Zomato is an easy target. The loss-prone firm just announced a new “instant” delivery service for food. The CEO writes in a blog post, “The fulfilment of our quick delivery promise relies on a dense finishing stations’ network, which is located in close proximity to high-demand customer neighborhoods. Sophisticated dish-level demand prediction algorithms, and future-ready in-station robotics are employed to ensure that your food is sterile, fresh and hot at the time it is picked by the delivery partner.” From our perspective, the text is a mind-boggling array of jargon; it may also sideline the fact that the initiative may be cost-unsustainable.

Are we sour on this market? Not at all. Headlines tied to IPO monetization are an altogether different issue than discussing the investment-return potential of young, privately-held companies. Local startups assuredly are not guilty en masse because some of their heavyweight brethren suffer from delusions of grandeur. What we are seeing here is a market in transition, towards one that is more rational and transparent. And that is good news for institutional and retail investors, both in India and worldwide.

For the record, we are drawn strategically to the Indian startup ecosystem. Our focus remains on smaller startups that are less impacted by the undertow of global capital. We look to ones that are at work in specific niches within the local and regional economy, not those aspiring to be international poster children. ■

Our Vantage Point: Risk-tolerant investors should be measured in their criticism of Indian market developments. Debate and disclosure will support stronger fundamentals over time.

Learn more at Reuters

© 2022 Cranganore Inc. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of any material on this site without written permission is prohibited.

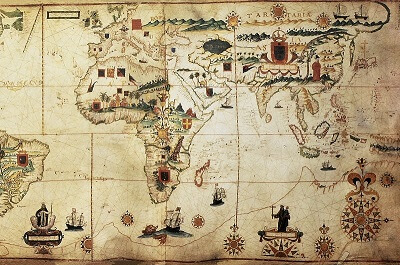

Image Credit: Immimagery at Adobe Stock.