Tehran’s ability to project its stature across the Middle East has been severely curtailed in recent months because of the economic collapse at home. Most analysts expected to see a newly-assertive Iran in the wake of the US assassination of General Soleimani last December. If anything, the opposite has happened as Iranian authorities focus on the failing domestic economy.

Economic activity in Iran this year is widely unpredictable. In mid-April, the IMF suggested that the economy could contract by 6% in 2020, following declines of about 8% in 2019 and near 5% in 2018. The actual decline this year will be much worse. The downside risk is amplified by three factors:

► Oil Prices. Tehran assumed a $50 a barrel oil price in its original 2020 budget. While prices are recovering from the demand shock in April, most experts assume they will settle at about $40 a barrel by year end. Iran has long sold volumes of oil at below-market rates in the black market, but even that adeptness may not help in this global setting.

► Coronavirus. Iran was an early epicenter for Covid-19, given its fluid ties with China. Yet, economic conditions forced it to reopen in late April. The nation has now seen a resurgence of cases, especially in provinces distant to Tehran. Officially, the cumulative death toll is about 7,000 as of mid-May. Insiders say the number is much, much greater.

► Domestic Unrest. Iranian society has been severely strained after protests against the government last November. Those demonstrations began over a sharp increase in gasoline prices; they quickly lead to the most severe crackdown by security forces seen since the Islamic Revolution some 40 years ago. As many as 500 people may have been killed.

These issues coalesce in the inflation rate, which Iran has estimated to hover around 35% in 2020, representing a slight improvement over the 40% or so seen in 2019. In reality, the figure for 2020 will likely accelerate unpredictably, leading to further collapse in the Iranian rial. The currency has been bouncing off the historic low seen in September 2018.

Tehran is desperate for cash. It ran the risk of US military intervention in sending five tankers of oil to Venezuela in late May. For Iran, longstanding ties between Caracas and Tehran are far less important than the gold and hard currency that the Maduro regime used to pay for the shipments. For its part, Washington may have deflected its dissatisfaction with the Iranian-Venezuelan deal as quid pro quo for Iran’s implied support for the recent ascent of a pro-US prime minister in Iraq.

Tehran is unlikely to distract its citizens from domestic problems by asserting itself more forthrightly on the international stage. One key reason is that leadership in Iran would assuredly celebrate a Trump defeat in November, given the administration’s debilitating, hardline approach to Iran. Trump sent the Iran economy spiraling into recession when it abandoned the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal in the second quarter of 2018.

From the Iranian perspective, leadership seems intent on promulgating a non-confrontational stance with Washington, at least temporarily so. They acknowledge that an aggressive Iran is de facto fuel for the Trump re-election campaign. We suspect that President Rouhani would prefer to negotiate with President Biden next year. ■

Vantage Point: Iran must focus on repairing the extreme damage to the domestic economy, rather than grooming its international advantage. One essential ingredient of that strategy is to work with a more accommodative administration in Washington.

Learn more at The New York Times

© 2020 Cranganore Inc. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of any material on this site without written permission is prohibited.

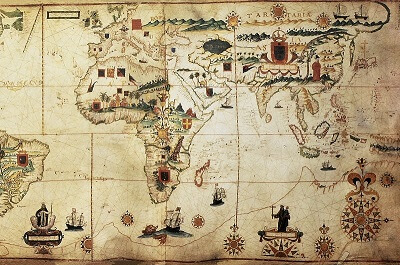

Image shows propaganda outside the former US embassy in Tehran. Credit: Nicolas De Corte at 123RF.